© Andy Singer

A contribution by Andy Singer

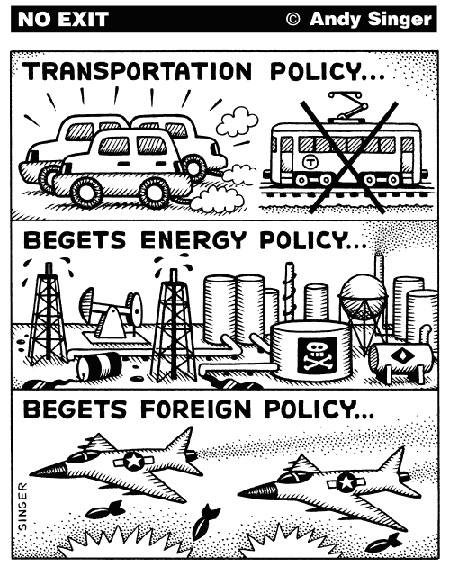

By now, it should be obvious that private automobiles are environmentally unsustainable. Yet many people still cling to the fantasy of “Green Cars”. Such people tend to focus only on alternative fuels and the emissions that come out of a car’s tail pipe. They ignore the fact that half the greenhouse gas and pollution a car will emit during its lifetime is created in its manufacture and disposal …and in the manufacture and maintenance of the roads on which it travels. The plastics in a car’s body, interior and tires, the steel in its frame, the lubricants it uses, and the asphalt and concrete it drives on all require petroleum to manufacture and maintain.

The focus on alternative fuels and tail pipe emissions also ignores other unsustainable aspects of automobiles. Salts and de-icing agents used to keep roads free of ice and snow are increasingly polluting our waterways and leaching into wells and drinking water. Cars kill more animals that hunters and experimenters combined—hundreds of millions per year, many of them endangered species. They kill over 45,000 humans each year, just in the USA and permanently maim millions more. The roads they travel on and their massive space requirements (for parking and maneuvering) destroy wild lands—blighting them with sprawl. At the same time, these space requirements also destroy dense, vibrant inner cities– blighting them with parking lots, traffic, and noise, taking away space that could be better used for housing, retail and non-transportation purposes. This creates inefficient communities because the farther apart people live from each other the more resources, energy and time must be spent transporting them to their jobs and essential services. Smaller electric “Smart Cars” won’t eliminate these problems and they won’t eliminate the threat of global climate change, the US dependence on foreign oil or even traffic congestion.

The solution for climate change, air pollution and oil dependence is simple—we need to get people to stop driving …or drive a lot less. This requires better land-use laws that promote denser, walkable/bikable communities and major investments in public transit to connect these denser neighborhoods, towns and communities to each other.

To fund these land use and transportation changes, we need to tax driving (or fuel use) at a rate that reflects its true cost and use the proceeds to subsidize automobile alternatives. We’ve known this since the early 1960s and countless books have been written on the subject.

Yet, despite this knowledge, we continue to build new roads and highway lanes. The Federal stimulus package contains over $15 billion dollars for new highways and bridges, even as the existing highway infrastructure crumbles or collapses from lack of maintenance.

Why is this? Why are we still building new roads despite all the evidence that doing so is suicidal? What are the political forces that prevent us from moving in the direction of progressive transportation policy? To answer this question, we need to know the history and the role that state departments of transportation, turnpike authorities and highway agencies play in transportation politics.

Prior to World War Two, the bulk of the country’s population lived in cities or towns. Suburbs existed but they were built around suburban rail stations and were fairly dense and walkable. Automobile manufacturers like General Motors had exhausted the rural and suburban market for cars and were looking for ways to sell cars to city dwellers. In 1923, General Motors’ president Alfred Sloan, said, “(the leveling of demand for new cars) means a change from easy selling to hard selling …(it is necessary to do nothing less than) reorder society, …to alter the environment in which automobiles are sold.”

Because people in cities had great public transit and interurban rail systems, GM and other auto makers decided that they needed to eliminate these systems or convert them to buses, thus inducing urbanites to buy cars.

GM began building buses as early as 1925 and formed and owned a controlling interest in Greyhound. For years it tried to buy up urban rail transit systems on its own and convert them to buses but this was going too slowly. So GM got together with Standard Oil of California, Firestone, Mac Truck and Philips Petroleum to form and finance a front

company– National City Lines– whose job was to buy up urban rail networks and convert them to buses.

They also lobbied for two important pieces of the legislation. The first was the Hayden Cartwright act of 1935. This required states to dedicate their state gas taxes to highway building, rather than putting them into the state’s general fund. This ensured a steady supply of money for new highways.

The second piece of legislation was the “Public Utilities Holding Company Act” of 1935, which required electric utilities (who owned most of the rail transit systems in the US) to sell off all their streetcar lines. With hundreds of streetcar companies dumped on the market, simultaneously, in the midst of a depression, they could be purchased very cheaply. GM’s front company National City Lines was thus able to buy up and dismantle rail transit systems in over 200 US cities.

In 1949 GM and its partners were convicted of conspiracy, in a Chicago court– a conviction that was upheld by a federal appeals court. Unfortunately, the punishment for destroying America’s transit systems was a slap on the wrist. Each company got a $5000 fine. No one went to jail …and the companies pocketed BILLIONS of dollars from the increased sales of cars and buses.

This is very much like what Microsoft did to its internet competitors in the 1990s (only much worse). In both cases, companies conspired to destroy the competition. By the time the legal system caught up to them, (through endless appeals), the competition had been eliminated and Microsoft or GM had changed the facts on the ground, making any fines irrelevant.

So auto manufacturers had a big role in destroying public transit. There were other factors, but public policy and politics were big ones. Having done this, the auto manufacturers needed more roads and highways for their cars. In 1920’s and 30’s America, building roads across county and state lines was legally and practically very difficult. So carmakers and the car clubs they created (like Triple A) turned to state and federal governments.

In this 1920s photograph, the man on the left is Robert Moses, then a little know government bureaucrat in New York State. Beginning in 1920, Moses helped successive New York governors to streamline state government and literally created the modern government “Agency”. He was also the first to create the modern highway department or “Authority”. In the early days, the preferred way to finance roads and bridges was with tolls. “Authorities” were government-sanctioned corporations that borrowed money by issuing bonds to pay for the construction of a particular road or bridge. The bonds were paid off by charging tolls.

Because drivers flocked to the new roads and bridges in record numbers, banks quickly realized that toll roads were a great investment and they became willing to lend Moses (and other state highway agencies) huge sums of money based on projected toll revenues. All this money built yet more roads. More importantly this money represented tens of thousands of jobs …for unions, engineering firms, construction firms, lawyers and public relations firms.

The ability to hire all these employees, gave Moses and other agency managers incredible political power. The highway agencies were no longer beholden to politicians to give them money. Quite the opposite, their control over toll revenues gave them power over the politicians and enabled them to extort even more money out of state legislatures.

One man who learned this from Moses was Franklin Delano Roosevelt. He’s seen here, sitting to the right of Moses, when he was governor of New York. When FDR became president in 1932, he borrowed many of Moses’ ideas and created federal agencies like the WPA and the Bureau of Reclamation, to help revive the US economy. He also borrowed Moses’ love of the automobile and many of the WPA’s projects were highway projects and bridges for cars.

Prior to Moses and FDR, political power lay strictly in the hands of the wealthy and in physical communities. If a party boss wanted to be reelected, he had to give jobs, money and graft back to the community in which he lived. In the new system — the agency system — political power lay in broader groups like unions, professional trade associations, and interest groups associated with a particular agency. All of these groups went across physical community boundaries. Thus, political power ceased to be community based. A party boss could now put a freeway through part of his neighborhood, or destroy it entirely and still be reelected. In the new system, civil servant agency chiefs and the agencies themselves wielded ultimate political power. Politicians came and went, but the chiefs and the agencies remained. Sometimes the politicians could control the agencies, sometimes they couldn’t. Term limit laws in many states have only made this problem worse.

To this day, much of what happens in politics is agency driven. You have intelligence agencies, defense agencies, energy departments, state university systems, housing authorities, space agencies, each with its own constituent base. Defense agencies have created a “military industrial complex”. The Bureau of Reclamation and its dams and canals have created a vast web of interests around irrigation and water policy and highways have created what I like to call “The Highway industrial complex”.

The nature of agencies (like private businesses) is that they try to grow larger and more powerful in order to get more money and jobs for themselves. Agencies that have external sources of revenue, outside of legislatures, have more political power. State university control of tuition dollars and private research grants would be an example of this. Agencies that don’t have external sources of revenue have less power, like certain welfare agencies that are entirely dependant on the legislature for their budget. By the mid 1950s, highway agencies had managed to get exclusive control of billions of dollars in state and federal gas taxes. In this way, they became the most powerful political force in state politics. Politicians who crossed a highway agency were quickly ejected from office. Engineers or public officials who crossed them often had their careers ruined.

This basic paradigm of revenue control and agency politics is the reason that America has built and continues to build so many roads. It’s the reason that little or no money goes to transit and that the number of cars, oil consumption and sprawl continues to grow.

In Minnesota, the Minnesota Department of Transportation or “MnDOT”, for short, can spend over $5 BILLION dollars per year, much of which doesn’t even pass through the legislature but comes directly from state and federal gas taxes. To give you an idea of how much money this is, the entire state budget of Minnesota was only $26 billion in 2003. So highway spending was almost a fifth of all state spending! MnDOT’s control over this money gives it incredible political power. To ensure this power, it wrote a provision into the state constitution MANDATING that state gas tax dollars have to be spent on highways. The agency literally owns legislators– people like Mark Ourada, a former Republican state senator whose private road-building employer received 74 million dollars in MnDOT contracts. They introduce legislation on the agency’s behalf and generally do its bidding. To quote Kent Allin:

“The culture of MnDOT is to act the bully, throw one’s weight around and villainize anybody who stands in your way and not worry about wasting tax dollars. …MnDOT is trying to bully us into giving it exactly what it wants, regardless of whether it is lawful or responsible to do so. I believe we have been pushed to a point where we either assert our oversight role …or tacitly admit that we are totally ineffectual in that role with respect to MnDOT.”

Kent Allin was a 21-year state auditor who was fired in 2002 for blowing the whistle on no-bid MnDOT highway contracts.

This same sort of thing happens in most other states …and there are many behind-the-scenes stories suggesting that other state DOTs operate in much the same manner -–using their political muscle to push through new highway projects and bully their opponents into submission. They do this either directly or through local Metropolitan Planning Organizations (MPOs). If you are interested in learning more about highway agencies, I strongly recommend “The Power Broker” by Robert Caro. It’s the most detailed examination of highway agency history ever written and it won a Pulitzer Prize. Outside of a few reforms in New York State, little has changed since the book came out in 1974.

So, if we want to stop sprawl and get more money for transit, we need to stop highway agencies from building roads. There are two strategies for doing this. The first is through “road pricing”– the use of taxes and tolls to try and reduce demand. Now, on the surface, this sounds logical– increase driving costs and people will drive less. But the key is who gets these increased fuel tax and toll revenues. Right now, it’s the highway agencies that are getting this money so it just gets used to build more highways.

Highway agencies have always used their financial and political clout to squeeze still more money out of state legislatures– either in bonding bills or as outright appropriations. When the economic downturn hit in 2000, states began to run huge deficits. Suddenly there was no more money to squeeze. In desperation, highway agencies began turning to other schemes to generate new revenues for highway construction. One of these consisted of bringing back toll roads in what they refer to as “Fast Lane Tolls.” In this scheme, DOTs issue bonds to finance the construction of special “fast lanes.” Commuters who want to use them pay a toll, which goes to paying off the bonds. Once the lane is paid off, it reverts to a normal lane.

The highwaymen sold fast lane tolling to voters by implying that it was “Road Pricing.” But true “Road Pricing” is designed to deter people from driving at certain hours or in certain places. “Fast lane tolls”, by contrast, are merely a way to finance new highway construction. Fast lane tolling was slipped into the federal highway bill a few years back. Environmentalists and activists either failed to notice it, until it was too late, or didn’t oppose it, thinking that it was “Road Pricing”. The NY Times predicted fast lane tolls would pump at least 50 billion dollars into new highway construction over the next ten years. State versions of the legislation have passed or are pending in many states including Minnesota. Additionally, DOTs are converting HOV lanes into “Hot Lanes”, allowing single occupancy drivers to use the lanes if they pay a toll, generating additional revenue for new highway projects.

Clearly, the moral of history is this– Tolls and gas taxes are useless at deterring highway construction unless the money goes directly to transit or goes into city or state general funds, where politicians can control it. If it goes back to highway agencies, more highways will be built and the agencies will only gain more political power.

In general, it’s better if politicians control tolls and gas tax revenues rather than the highway agencies themselves. This is because the politicians are elected and are at least somewhat accountable to voters. By contrast, highway agency directors aren’t accountable to anyone. It should be noted that true “road pricing” only exists in London, Singapore and a couple of cities in Scandinavia and Latin America, where toll revenues actually go to automobile alternatives. So, the devil is in the details of most legislation and you need to look where toll revenues are going to go. Also, before you can redirect toll revenues, you have to eliminate or amend the state constitutional provisions that dedicate them.

The second way of controlling highway agencies does exactly that. It was partly inspired by what happened in New York City and is best represented by a piece of federal legislation called “ISTEA”. In 1970 Governor Nelson Rockefeller was able to combine Robert Moses’s New York City highway department with New York City’s transit agencies to form the Metropolitan Transportation Authority or “MTA”. Under the new structure, toll revenues could be used to subsidize transit …and the new agency no longer had a stake in building roads. It could just as easily build transit projects, since, either way, it got to spend the money and grow itself.

© Andy Singer

In 1991, the U.S. Congress passed “ISTEA”– The Intermodal Surface Transportation Efficiency Act. For the first time, a portion of federal gas tax dollars were set aside for non-automotive projects. If a state highway department wanted to get this money, it had to come up with a non-automotive project on which to spend it– either transit, commuter rail, bicycle or pedestrian. The thinking was that this would give state highway departments an incentive to diversify and become truly integrated “Transportation” departments– thus forcing a change of culture within the state agencies.

ISTEA paid for bikeways, light rail and commuter rail systems in dozens of US cities including parts of Minnesota’s Hiawatha light rail line. ISTEA also produced a small shift in the culture of highway agencies, since many state DOTs hired new engineers and coordinators who specialized in transit, bike or pedestrian engineering. Often, however, they were relegated to a lower status within the agency and, as always, new highways kept getting built. The states that did best tended to be the ones that already had strong transit agencies and substantial transit infrastructures.

This first incarnation of ISTEA set aside a third of all federal gas tax dollars for non-automotive projects– nearly $50 billion out of a $150 billion dollar 6 year budget. Six years later, when the act was reauthorized as TEA-21, highway spending was increased to $150 billion, while transit spending was kept flat. Loopholes were added that allowed off-ramps and other highway oriented peripherals to qualify as “Pedestrian Improvements”. Also, ISTEA left state gas tax dollars untouched, still firmly in control of state highway departments. The most recent incarnation of ISTEA – “SAFETEA-LU” — has only made matters worse.

We would need to beef up TEA to give 100% of federal gas tax money to non-automotive projects. Only then would we see a substantial change in state agency culture and an end of new highway construction. This is something we should try to do in 2009, when the act is reauthorized. Also, we need to introduce federally mandated targets for reducing “Vehicle Miles Traveled” (VMT). This way, “reducing driving” will become the standard by which we judge the success or failure of a transportation or land use project. Right now the standard is “Improving Level of Service” for cars, which is a disaster.

Lastly, as people drive less (due to increased gas prices and economic decline) gas tax revenues have fallen. For this reason and to do an “end-run” around state constitutional amendments dedicating gas taxes to roads, other taxation and transit financing schemes have been proposed. The main one of these, similar to “road pricing,” is to tax people based on how many miles they actually drive. Whether such schemes or even basic city road pricing will ever get started in the US is hard to say but New York City seems to be edging towards implementing some sort of road-pricing plan.

Thus, the best way to combat highway agencies is to cut off their money supply, partially or entirely, and integrate them with transit agencies. All or a portion of tolls and gas tax dollars should be diverted to transit projects and urban revitalization. We need to see the gas tax, in part, as a “Sin Tax”, similar to the tax on alcohol or cigarettes, where part of the proceeds are used to counteract the negative effects of driving. As we look for dedicated funding sources for transit and urban revitalization, we must look towards gas taxes, mileage taxes or highway tolls as a source of revenue and make the legislative changes that will enable this to happen. This will be politically difficult to do but, with the will and the organization, it is definitely possible.

Working in our favor is the fact that building and maintaining fixed rail transit provides even more jobs than building highways. With skillful political leadership, a broad array of groups can be led to support transit projects and improved land use laws, including many of the same groups that currently support highways– unions, contracting firms, architecture firms, heavy industries and groups representing voters who are unable to drive, like the elderly and handicapped.

We are facing a serious environmental and resource crisis. So called “green cars” might buy us a little extra time but they are not a serious solution. The only real solution is to make the political and funding changes that will enable us to overhaul our nation’s land use and transportation systems. With a little luck and hard work, maybe we can pull it off.

Andy Singer, 8.3.09

Andy Singer is a cartoonist and alternative transportation activist in Saint Paul, Minnesota. You can see more of his work at http://www.andysinger.com/

© Andy Singer

Filed under: The End of the Road | Tagged: book, drawing, future vision |

With you all the way!

The following was written yesterday to the AFL-CIO Head of Building Trades Unions, before AFL-CIO came out with its typical Militaristic Capitalist lackey policy pronouncement in support of Boeing’s contract bid for in-air jet fighter fuelers/tankers.

But, for what it’s worth:

Mr. Ayers:

There was a report this morning that 50,000 people showed up at Cobo Arena in Detroit for housing, energy, and food assistance. This is a marginally reported manifestation of a huge problem that has been going on for years, and accelerating recently; the plight and “invisibility” of those dispossessed by the schism between the rich, the owning classes, and the losses in livability for the working and non-working (many former “middle class” elevated to such success by the former strength of unionization) poor as the inflationary spiral of Capitalism shed many and left them and others behind in the day to day struggles and realities of the “supply-side” and post-“supply side” eras.

Whereas, hope is hard to find, I found a sliver of it in the new AFL-CIO’s leadership proclamation of a mission to “organize the unorganized”.

We desperately need working class leadership in this country and the world. We need to commit and dedicate to the famous old slogan of the International Workers of the World (sic) [IWW], “One Big Union”.

Given resource limitations, economic collapse, population pressures, and ongoing and increasing tensions brought about by environmental inequality, now more than ever we need to enunciate, inculcate, and commit to world unity and cooperation. The explicit principles to underlie such are related later in this letter.

I offer the following for your consideration, inter-organizational and related communications, and commitment relative to policy, program, and project development:

I am named after my great uncle, Mike Misenti, who worked and fought? his way from humble beginnings as a mason to President of the Building Trades Union, and later President of their Pension Fund, in the State of Connecticut.

Mike Misenti didn’t care what “his folks” were building, as long as they were building. That is my major complaint with Labor Unions, their need to self-perpetuate, and offer blind loyalty and complicity with less than optimal corporations/contractors and the latters’ self-interested profit motivated projects and industries that are sometimes, if not often, counter-productive to social/environmental goals..

Don’t get me wrong, I consider the interests of workers of all “stripes” and the poor to be of the utmost importance. However, in this era of post-peak oil, climate change, inequality and the tensions that such brings, and the perception of hopelessness that are held by and for youth and for the children, it is necessary that we allocate scarce resources in the most optimal ways and means possible.

We must recognize the fossil fuel age and the subsequent overshoot in automobile and airplane use as a historical exception that must be phased into perspective.

If we want to conserve precious fossil fuels for priority uses such as solar assisted heating, cooking, electricity generation, cooling, agricultural inputs, durable products, necessary industrial processes, inter-community and inter-regional transport within a paradigm of relocalization for all communities and regions (moving towards self-sufficiency), and preserve the luxury and convenience of occasional automobile and airplane travel in a manner that explicitly adjusts for economic disruption, then we must plan and implement.

We need to see the study and practice of Resource and Regional Planning beyond the historical complicity, and at best mitigation of, the irrational Capitalist growth paradigm that does not recognize and/or respect a finite planet whose limits that we are fast approaching. We must enter an era of Resource Allocation based on the explicit principles of meeting human needs, inclusion, equity, humanity, quality of life, environmental/public health and wellness, sustainability, economic democracy, and peace.

The key to a bountiful green (building) economy is the reversal of the thirty, fifty, one hundred year trend of sprawl development in the United States.

By rebuilding neighborhoods and reallocating goods and services to those renovated neighborhoods (made walkable, meaning that the great majority of Americans will be able to get what they need within walking distance of their homes), we can succeed.

Such a tremendous dedication of resources will be a boom to the building trades and other sectors and will create the effect of reducing automobile usage by 80% in the next 20 to 40 years. Neighborhood commercial, community and work/telecommute centers will be centrally placed in what are now alienating, automobile dependent, strictly residential areas, alleviating the problems associated with post-peak oil and climate change and bringing with it the quality of life associated with communities and neighborhoods, that most individuals and families currently lack.

If we do this, we can take the opportunity to retrofit for

weatherization, passive solar design (heating and cooling),

electronic environmental controls, solar assisted hot water

applications, limited PV and wind applications, etc.

Also, if done correctly, we can make changes in ownership

arrangements that are much more fair and just, and work towards an equitable distribution of wealth among neighborhoods.

It is important that we fundamentally reassess our economic system and replace the current economic/finance system with one that targets the needs of the current residents, and not, for-profit speculation.

Because of the terrible inflation of real and capital assets that is

a product of the speculative modus operandi of the Capitalist system, it will be fundamentally necessary to reform our economic/financial system by consolidating private (while rededicating them as quasi-public) real and capital assets and equity and writing way down the “market value” of those assets.

After completing that awesome task, we could proceed with a “plan and implement” economy dedicated to meeting the needs of the indigenous populations of all communities: inclusion, humanity, equity, quality of life, environmental/public health and wellness, sustainability, and peace.

Mike Morin

Eugene, OR, USA

http://www.peoplesequityunion.blogspot.com

wiserunion@earthlink.net

(541) 343-3808

)))))))))

Marvelous, Andy! Thank you!

Also I thank for that words and your images!