IT’S A NEW STAGE NOW, BABY

INTRODUCTION. (Joseph ; Amy)

I’m Joseph and I’m a car dealer. I feel like I’m introducing myself at an addiction support group. President G. W. Bush’s recent admission that we’re a nation addicted to oil was not the first time I noticed. I’ve been in the business for 25 years. I’ve been on the planet 52 years. Nothing in my business is new.

I was born in 1956. That’s right about the time that the Interstate Highway system and suburban migration changed the American landscape. Each family was capable of owning its own personal transportation device, a car.

People were moving around fine without cars. I was born in New York. Mobility takes many forms there. People take busses to trains to subways and perhaps a taxi. Ferries still carry cars and people but just imagine how many people used to use ferries to and from Manhattan Island. There weren’t very many bridges to Manhattan until planners were convinced that they’d be full of cars.

I live in the Pacific Northwest now and enjoy my visits to Seattle, perhaps because it reminds me a bit of home. I love the Puget Sound. I had considered moving to Seattle when I moved west but the traffic congestion also reminded me of home and one of the primary reasons I was leaving in the first place. I was spending too much time in the car and I think that’s low quality time.

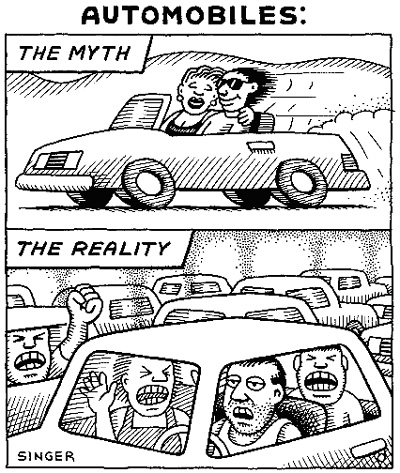

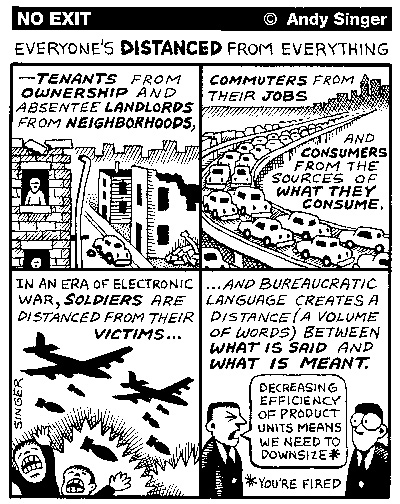

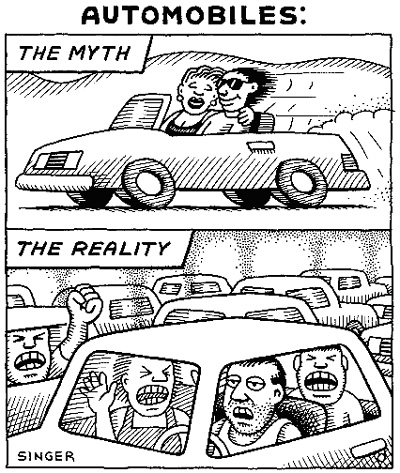

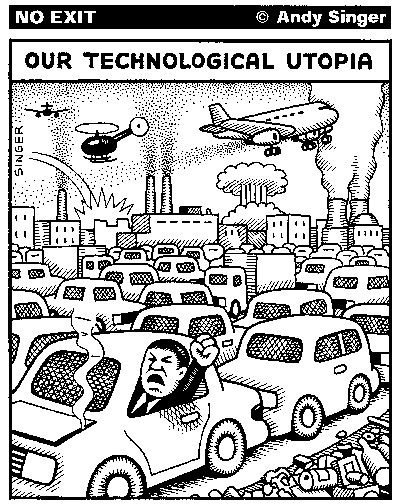

Americans have romantic notions of cars. Even though they drive on ugly roads, past ugly mills and factories, billboards and strip malls, they try to imagine the glory of the Open Road. We are great at pretending. Any moment now I’ll see a beautiful landscape, roll down the window and let the wind blow back my hair. Snow covered peaks and Sonoma desert sunsets are captured on TV and I’m sure I’ll see one around the next bend. Our expectations are not created by life. They are created mostly by television.

It’s sad but true that most of the wonders Americans feast their eyes on are seen from the car. We don’t hike those peaks and we don’t camp in the desert and we don’t fish those rivers. We satisfy ourselves with a drive through Vermont in the fall.

Is this because we don’t care? Or are we afraid? Isn’t this because we have developed a full-blown, relatively unfettered capitalist culture that says we must always be pursuing growth, becoming bigger and better, have more than our parents, that the silver medal is simply not good enough? In other words, do we have a culture that allows us to get out of the car and enjoy nature anymore? We are barely retaining art, music and physical education in our schools, life is increasingly competitive; what is this teaching us about the most nourishing aspects of life?

Is it materially better to view those leaves from behind a windshield than sitting before a TV screen? Are people meant to view beauty or experience it? Do we spend so much time working to afford mobility and modern convenience that we’ve no time left to savor an experience. Must we substitute a snapshot of it?

Is a vehicle a means to an end, in this case literally meaning to get us from here to there? Other things can move us and that’s both literal and figurative. A vehicle is a tremendous metaphor.

This is America. Here we proudly claim we’ll fight and die for freedom. We find mobility and freedom synonymous. This attachment extends wholeheartedly to our cars, our right to buy what we want and drive what we want. It’s changing; people are seeing the wisdom of more fuel efficient cars, but that psychology is absolutely tied to the price of gas, artificially low right now and within a few years absolutely going to turn around and sock us. Peak oil is here, and few understand that gas prices are artificially low currently, and for only a brief moment. Still, the car culture is cult-like. Speak out against cars and you’ve got enemies from big oil to the Big 3, not to mention the truckers, classic car buffs, motor-heads and bikers. They’re everywhere. Now I think we could include Tahoe driving soccer moms too. We just can’t seem to imagine any other way of doing our daily business.

Ok Joseph, lets start right here, and I will do my best not to be coy and simply feed you lines. I am a parent and I work, right now from home. I drive A LOT. But I don’t love my car, and I expect many women in my situation would say that. Driving exhausts me. I can remember the thrill of learning to drive, but doing so every day, especially the multiple, repetitive trips to get my children, take them to events, drop one off and pick up the next, all the while driving right back up the hill I live on about 15 minutes from the heart of the city, well I hate it. Not only is it boring and mindless at middle age, it is uncomfortable as well as guilt producing, because I know that with multiple trips I am wasting gas.

But I put up with it like everyone else, because until recently I have not seen what my alternatives are. You make it sound as though we all have luxury vehicles that we adore driving as much as possible. My car is a work horse, and any luxuries it has, such as heated seats, I feel entitled to due to my various aches and pains – which most of us have by now (I am 51.) I live in a city that has a flat downtown but a hilly suburban residential area on almost all sides. My knees prevent me from biking (we tried a bike rack, I can’t lift bikes, ok so I need to work out more and get stronger, yet another ride into town to the health club for that.) The bus service comes remotely near where I live two times during the day: 7:45 a.m., and 3:45 pm. There is simply no way I could get by on those times. This is an argument for investing in new mass transit, not “shovel-ready” projects that do not shovel us forward!

We live in a frenzied, competitive time, and the current recession has only made us all desperate. We make trade-offs. Driving is the cost of having work that allows me to put my children first, and being at home means I am not close to where I need to shop during the week. Of course I try to conserve trips; I bet most of us do. We are not just tired; we really do not want the expense or the moral guilt from using gas.

I tried a hybrid; I really wanted to do the right thing. It was an uncomfortable car, and it did not get the fuel economy the company claimed it would. I feel terrible driving a regular, internal combustion car, and terrified about the major event that comes in a few short months, when my son turns 16 and we hand him the keys to the car. (Note: by the time this book went to print, those keys were a given.)

I don’t want your ideas to be unpopular. I have learned a great deal from you, and am convinced by your concerns. But you do seem to make it sound like the way out is easy, even quick. I dare to hope again, even after the painful lessons brought home by such urgently imploring illustrations in, for example, “An Inconvenient Truth.”

I believe the future depends on each one of us making the right choices, and that we are out of time to simply leave the solutions to our children. We already lost that battle; I was learning about pollution in grade school and was taught it had to be handled by us when we grew up. Right. I do have faith in our project and I think so many people want to do the right thing. It’s a matter of educating – our task here – so that people can come to see alternatives as I have now.

I imagine I could be the most unpopular man in America to suggest that it’s the end of the road! But that is what I am here to say.

I imagine I could be the most unpopular man in America to suggest that it’s the end of the road! But that is what I am here to say.

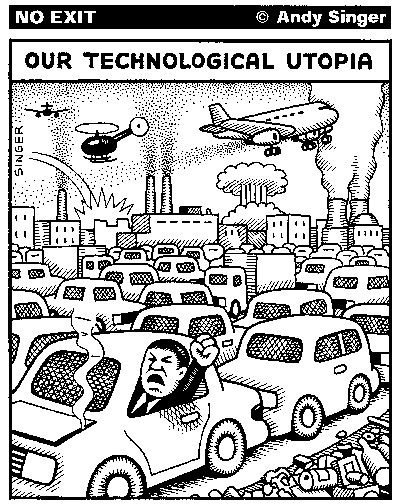

That’s right. It’s all downhill from here. We are past due when it comes to changing our models of mobility. We’ve fouled the air and water with our inappropriate, destructive methods of movement. We must change now because the rest of the world is about to follow that model and that would be suicide.

I put my 177 pounds into a 4000-pound vehicle to move me efficiently from here to there. Inappropriate and unnecessary. It’s got the power of 300 horses, but most of the time I could make the trip on one horse. Inappropriate and unnecessary? Overkill. Folly.

It’s got the technology to protect me from a hundred different threats from numerous directions. Of course, I could kill and maim so many others with it by hitting pedestrians or a school bus. But I’m not alone. Not only is my personal safety covered, much of the transportation infrastructure and regulatory policy is designed to carry my weapon (car) safely and efficiently.

I have an incredible amount of comfort within my weapon. I’ve Beethoven or The Beatles filling the air in crystal clarity. I’ve heated leather seats, automatic climate control, automatic cruise control, automatic lighting and even my windshield wipers do my bidding without my asking.

I’m not sure which came first but it’s clear that our vehicles are our living rooms today. People are working, moms and dads, all the time to pay for their vehicles that average 10% of income. If one works all the time, there’s no time to be in the living room. So now our phone is in the car, our kids watch movies in the car, our many beverages have a place of their own there and our meals are consumed while we race from here to there.

I absolutely telephone, write checks, drink hot chocolate and even eat my lunch on the run. I know these things are wrong, but I do not do them out of carelessness or callousness. I do them because as a working mother who wants to be there at 3:15 for her children, everything I do, from work to volunteering to exercise to doctor appointments and shopping is fit into so few hours. Why not wait for the weekends? Sports and more sports, with my children.

How did this insane lifestyle evolve? Though I love it, I hardly work just for fun. I work because we have three children to put through college, despite my husband’s fortunate salary and because of course our 401K is in smithereens. I work because I am driven to make a contribution and give back what my education and privileges have allowed me to become. But all this and parenthood too has meant driving is not a mere matter of convenience. To me it often feels like survival!

I am not saying you have put up a “straw man” argument, because I cannot argue in general with the materially self-indulgent nature of our American culture. In fact I think in many ways we have been lulled to sleep by it. But I do think that we also want to do better, that we have been deprived of zero emission cars for decades, and have not seen our alternatives. You are helping us wake up to possibilities; especially to the urgency and the possibilities of the moment.

Our love of cars and convenience has created the convenience store phenomenon. That’s what we call those stores that have terrible selections of the unhealthiest products at incredibly high prices. Doesn’t this sound like addictive behavior to you yet?

Oh yes, I was talking about folly. I was talking about the end of the road.

I imagine that we’re all conservative on some levels. We conserve our air and water, put nuts away like squirrels and know that inappropriate, destructive behavior is unsustainable. The way we’ve evolved our transportation systems and networks has been anarchic. We could not see today’s vehicles when we designed roads years ago. We didn’t have the best transportation planners, engineers and designers working on the project. It’s been a haphazard development, and some might claim that to be the reason things are so good.

But the result is a system of roads and expenses that support them that I believe to be at the end of its useful life. Roads can be decommissioned, utilized during a period of transition and saved as a neighborhood museum. Industries can re-tool. Priorities can be re-set.

Some people will be sad and some angry at the end of the road. Sadness comes, perhaps, from nostalgia, from the hearts of the romantics still wedded to their cars and roads. Anger comes from those who perceive that someone is taking away their weapon, or freedom, or comfort or power.

Some people are always looking down. They are proponents of the myth of scarcity. There’s not enough. It’s ending too soon. How will we deal with our shrinking pot of finite resources?

I suppose the points I am making do come from a sense of scarcity.

I suppose the points I am making do come from a sense of scarcity.

But not just of peak oil, which I am well aware of and care about tremendously. Nor do I want to be yet another American who lives a life, however hectic, at the expense of others all over the world. Yet life, even our freedoms, come in context. I am bringing up my family in a country that does, in its competitive culture, take my time, my peace, even my ability to act upon my deeper values, away from me. I sound like a relatively wealthy victim, I know, with a lovely middle-class house and lifestyle. I do experience our American culture as so wildly competitive now that children lose their childhoods to incredible pressure way too early. But I am not ready to trust some radically new lifestyle. So keep talking, but don’t be too cynical. Show me the way out.

Other people are looking up. They see an infinite number of options, solutions, ideas and alternatives. That’s the optimism I remember from school as the essence of being American. We don’t look down and say, “Too bad, there’s not enough oil. When oil burns it’s killing us. Let’s just burn it and fight over it anyway.” I was taught that we’re smarter than that. I was taught we are adaptive and rewarded by our bullishness.

That’s right, just like on Wall Street, there are bulls and bears. On these streets, Main Streets, the mean streets, real streets, we’ve got some serious change coming. Embrace the end of the road, embrace the change and ride it. Know that it’s coming and be a part of the solution. I don’t know about you but after 52 years, I’m ready to do the right thing and stop going along, just another part of the problem.

I want to embrace this idea; I will embrace it. But it is overwhelming. I still hold back on the hope that we can save this planet for my children and my future grandchildren, and yours. I would be lying to say I am without fear and doubt. I would not have signed on to this project with you, if I had no optimism in me. I have indeed seen the difference one person can make, and what a whole group of organized people who are prepared to work and sacrifice for the greater good can accomplish. Perhaps we are just planting seeds here, but I want more than that. Because our planetary and cultural challenges are absolutely dire, I want to see a difference now, before it’s too late.

I may have to rely upon your optimism while mine builds, and while I write to try, with you, to convince others that we can do this thing. Because I do agree with you, it is the end of the road as we know it. And I will start by saying I am up for experiments, but I am afraid. Of what? Change.

Filed under: The End of the Road | Leave a comment »

Many heritage activists and other citizens felt an Ontario Municipal Board hearing a decade ago over plans to build a multi-story condo in Port Dalhousie and rip down some of the old buildings in the area, including the now-gone Port Mansion pictured here, was stacked against them and…

Many heritage activists and other citizens felt an Ontario Municipal Board hearing a decade ago over plans to build a multi-story condo in Port Dalhousie and rip down some of the old buildings in the area, including the now-gone Port Mansion pictured here, was stacked against them and…

The aged wetlands in Thundering Waters Forest in Niagara Falls, Ontario – home to a diversity of wildlife – have been a target for something called “biodiversity offsetting” – code for destruction – by the Niagara Peninsula Conservation Authority. Will Ontario’s Wynne government give the green light for that destruction to happen?

The aged wetlands in Thundering Waters Forest in Niagara Falls, Ontario – home to a diversity of wildlife – have been a target for something called “biodiversity offsetting” – code for destruction – by the Niagara Peninsula Conservation Authority. Will Ontario’s Wynne government give the green light for that destruction to happen?

I imagine I could be the most unpopular man in America to suggest that it’s the end of the road! But that is what I am here to say.

I imagine I could be the most unpopular man in America to suggest that it’s the end of the road! But that is what I am here to say. I suppose the points I am making do come from a sense of scarcity.

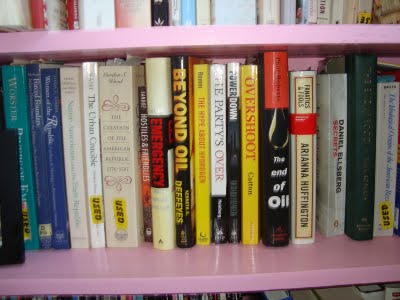

I suppose the points I am making do come from a sense of scarcity. Mini Peak Oil Library

Mini Peak Oil Library